Narrowing the gap between the share of men and women who work is one of the very important reforms policymakers can make to revive economies amid the weakest medium-term growth outlook in more than three decades.

With global growth predicted to languish at just 3 percent over the next five years and with traditional growth engines sputtering, many economies are missing out by not tapping women’s potential. Only 47 percent of women are active in today’s labor markets, compared with 72 percent of men. The average global gap has fallen by only 1 percentage point annually over the past three decades and remains unacceptably wide.

To blame are unfair laws, unequal access to services, discriminatory attitudes and other barriers that prevent women from realizing their full economic potential. The result is a shocking waste of talent, leading to losses in potential growth.

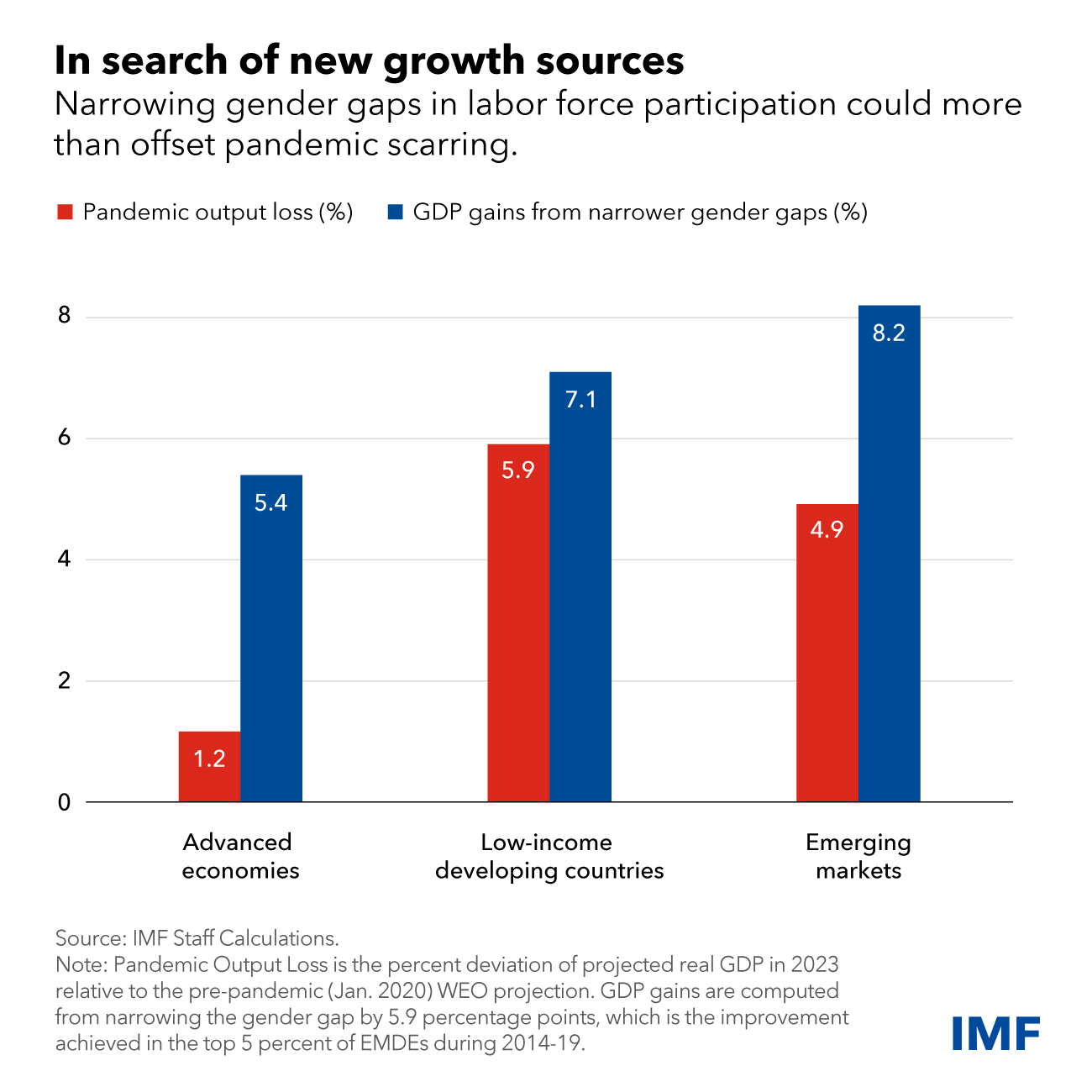

We estimate that emerging and developing economies could boost gross domestic product by about 8 percent over the next few years by raising the rate of female labor force participation by 5.9 percentage points—the average amount by which the top 5 percent of countries reduced the participation gap during 2014-19. As the Chart of the Week shows, that’s more than the economic “scarring,” or output losses, inflicted on countries by the pandemic.

Policymakers can of course lift growth in many ways, from governance reforms to strengthen institutions, to financial reforms to unlock capital for investment, as discussed in a recent IMF blog. Complementing these reforms with measures to narrow gender gaps would greatly amplify these returns.

Unfortunately, present policies do not come close to closing gender gaps. Many researchers say it’s inevitable that women’s labor force participation will eventually reach that of men, even if it takes centuries. But gender gaps are unlikely to ever close if present policy trends persist, as we show in a new research paper.

Our analysis of three decades of data shows that countries have made progress increasing women’s participation, but economies of all income levels experienced several setbacks—a result of shocks, crises and policy reversals. The pandemic, for example, eroded progress closing gender gaps, especially for women with young children. Setbacks like this cause scarring that slows and often reverses progress toward gender equality.

As a result, gender gaps in labor force participation will narrow but never close if countries continue on their present policy path. Gaps would remain large for most countries, exceeding 16 percentage points in one out of ten countries.

Countries must step up efforts to break down barriers to women’s participation in the labor market—such as limited access to education, health, assets, finance, land, legal rights, and care services. They should systematically take account of how macroeconomic, structural, and financial policy packages impact women. The IMF’s gender strategy aims to assist member countries in these efforts.